Energy: Measurement - Water

March 16, 2021

Measurement: Francis Turbine

When deciding what to measure for this project, I looked towards our lesson on motors.

I had no idea that you could use a motor to generate electricity, and I thought about how there are a ton of applications of turning kinetic energy into electrical energy.

I have always been fascinated by the ocean and I have always said that my shower’s water pressure could “power a house,” so it was obvious what I had to try.

Part 1: Small Turbine

https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:802284

The first thing I tried was printing a generic turbine from thingiverse. I wanted to experience a turbine in motion at a small scale.

I printed this to attach to my shower, but I first tested it on my sink (same thread/pipe size). Unfortunately, the water would just burst through it.

After sanding it down, I tried again, but yielded the same result. as such, I decided I needed to abandon my current trajectory.

Part 2: The Francis Turbine

I dug into google and started to explore how we harness energy from water.

Obviously, there were tons of different ways to do this. There was new tidal stuff, old watermill stuff, but the most common type of water turbine was the Francis Turbine.

The most basic way to describe this piece of equipment is that the water enters the enclosure, spins the turbine, then exits.

However, there are tons of turbines that work like that, so what is a “Francis turbine.”

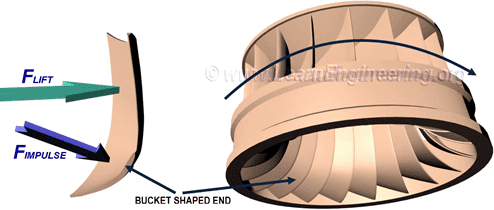

The main difference here is lift. The blades on this are specially designed so that when water passes through them, the impulse force of the water (impulse force is a force that exerts itself on something for a short period of time, in this case, each blade as it spins) against the blade, and the low pressure on the other side of the blade creates lift, which helps spin the turbine.

This special design is also made to not lose too much energy in the process.

These turbines are also often used where water has a lot of vertical potential energy, the higher the source, the better. That said, it operates efficiently at a wide range of conditions, so it is responsible for 60% of global hydropower generation.

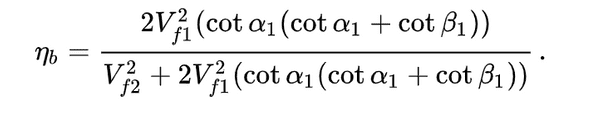

Unfortunately, the actual calculations of this are a bit above my calculus skills, but I have read a decent amount about it in order to understand it:

Essentially, the flow velocity remains constant and equal to its velocity at the start of the inlet tube. From here, a common turbine equation can be used to calculate the energy transfer to the rotor per unit mass of the fluid. Then after adjusting for kinetic energy loss (and ignoring friction), we can see approximately how much energy.

This is not the type of stuff I have the ability to measure at the moment, but it is safe to say that my shower does not actually produce as much energy as I had thought.

The water pressure in a shower is very dependent on the shower head “extruding” the water from small holes. Even then, it’s not super likely it would be a ton of energy. That said, I was not sure about this until I tested it.

Part 3: My Francis Turbine

https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:2963671

This is the piece I ventured to try measuring with. I was able to use a 3D printer to print everything (which took about 25 hours).

The main pieces above fit snugly, which I knew wouldn’t fly, so I attached the turbine to a drill and began to sand it down uniformly.

I did this for a long time, but eventually I was able to easily spin the turbine. So, I put it together.

I had done enough research, and seen what pitiful water pressure my shower has without its head to know I needed something that could provide a stronger impulse energy, so I got my garden hose with a pressure changing cap.

Unfortunately, this went as such:

I tried to sand it down more, but I just could not get it to spin. I am confident what was happening was a combination of improper flow through the turbine and improper/insufficient level of refinement on the turbine.

Part 4: Conclusion

As I said above, I think I was fighting an upstream (wink) battle. A 3D print can’t really achieve the level of precision required of something that relies on pressure differential to function.

Furthermore, frictionless environments rarely exist, and trying to achieve that with something as simple as a 3D print is unrealistic.

That said, I think I have a better understanding of what it takes to generate energy from water as well as the physics behind turbine related energy.

I would like to find a more compact way to harness water pressure (maybe a more sophisticated fabrication?). Ideally, I could use this knowledge to create something that

Written by Philip Cadoux, current ITP student and Creative Technologist. Follow me on Instagram